Evicted by Luxury

- Vedant Mangal

- Apr 20, 2025

- 3 min read

Australia’s deepening housing crisis has become one of the most critical and emotionally charged issues in the lead-up to the 2025 federal election. With sky-high rents, record homelessness, and the disappearance of affordable housing options, voters are demanding action—and the political stakes couldn’t be higher.

Nowhere is the crisis more visible than in Sydney, where historic boarding houses, once a lifeline for low-income residents, are vanishing under the weight of gentrification. In suburbs like Paddington and Dulwich Hill, long-term tenants are being displaced to make way for luxury apartment developments. These transitions are not just architectural; they are social upheavals, with the most vulnerable Australians paying the price.

In one striking case, elderly and disabled residents of a Paddington boarding house were served eviction notices after a developer bought the property, with plans to convert it into a block of luxury flats. Despite community protests and pending legal proceedings, residents were told they must vacate by February 1st—regardless of the court’s ruling. "I’ve lived here for 14 years," said one resident, “and now I have nowhere to go.”

In Dulwich Hill, 75 tenants—many of them on Centrelink and pension support—were forced out when their boarding house was shut down and later reopened as a student hostel charging double the rent. Critics argue that this trend, often described as "renovictions," allows landlords to bypass tenancy protections and profit from a broken system. The NSW Tenants’ Union has warned that these loopholes are widening, while housing advocates have called for an immediate moratorium on boarding house redevelopments.

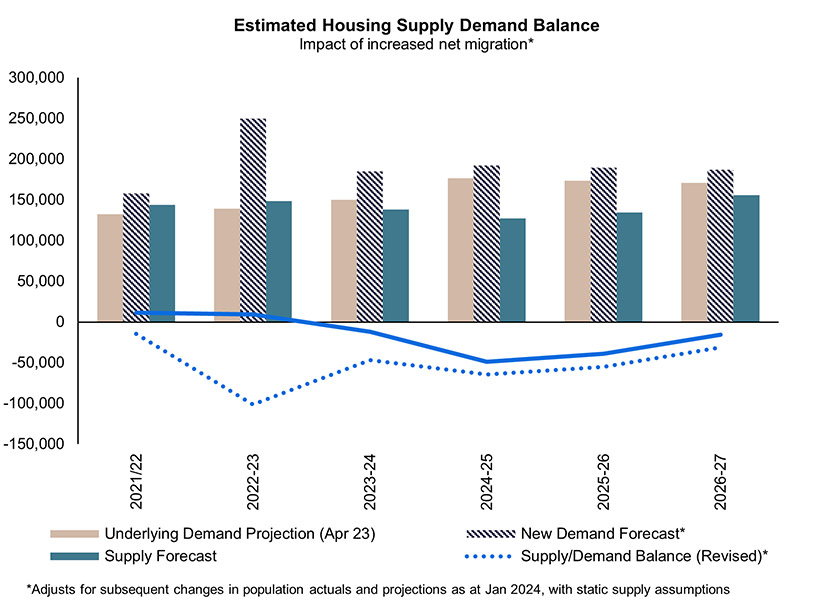

The boarding house crisis is only one thread in a much larger and more tangled housing problem. Across the country, rents have surged at double-digit rates, while housing supply has failed to keep up with demand—particularly for low- and middle-income earners. More than 180,000 households are now on social housing waitlists, and Australia’s homeless population has surged past 122,000, according to the most recent census.

With pressure mounting, both major political parties have been forced to respond. The Albanese government has committed to constructing 1.2 million new homes by 2030 through the $10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund. Yet critics argue that the plan is overly ambitious and lacks adequate provisions for genuinely affordable or public housing. The Coalition, meanwhile, has unveiled a proposal to allow mortgage tax deductions for first-home buyers and investors, a move that some economists warn may further fuel demand without solving the root issues of supply and affordability.

Beyond policy debates, a growing grassroots movement is shifting the conversation. The People's Commission into the Housing Crisis—led by researchers, advocates, and residents—has called for a bold rethink of housing as a human right, not a commodity. Their key recommendations include building 750,000 social homes over the next 20 years, implementing rent freezes in high-pressure zones, and closing tax loopholes that incentivize property speculation.

The human cost of inaction is becoming harder to ignore. “We’re not just talking about numbers,” said housing justice advocate Kira Newbold. “We’re talking about real lives, families forced to live in cars, pensioners sleeping in parks, and young people priced out of their own communities. If this isn’t an election issue, what is?”

With the federal election just months away, housing affordability has become a litmus test for leadership. For many Australians, the vote in 2025 won’t just determine the next government—it will determine whether they can afford to live in their own country.